Population growth — and climate change — may force Texans to change how they find and use water

Regional planners in Dallas-Fort Worth are looking for ways to ensure residents have enough water for decades to come, but there’s not a simple solution.

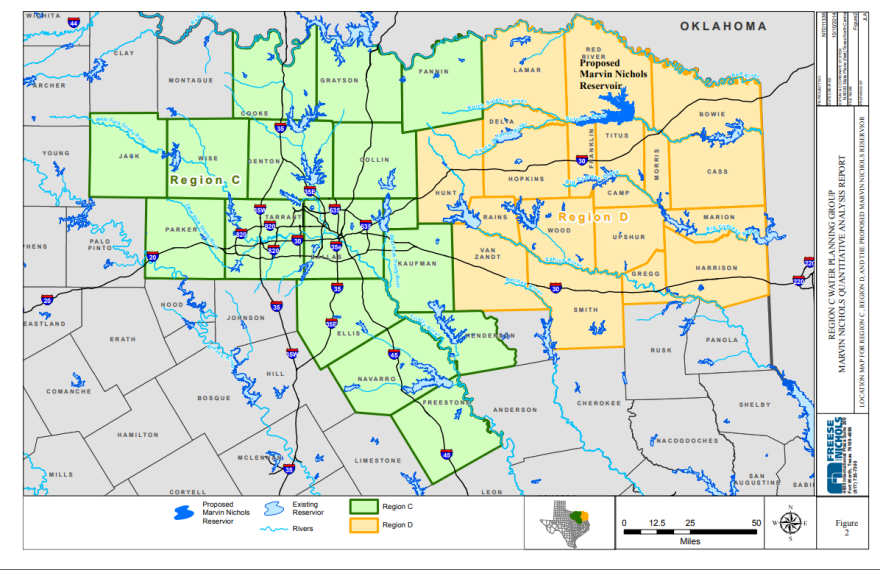

The Marvin Nichols Reservoir, according to the people who want to build it, would likely keep the Dallas-Fort Worth metroplex watered into the 22nd century.

It would also flood Gary Cheatwood’s community in Northeast Texas.

“All this will be deep underwater here,” Cheatwood said this summer as he drove over tree-lined country roads in the Sulphur River Basin. “Very deep.”

Cheatwood, who turns 83 this month, has lived almost all of his life in the area of the proposed lake. He knows which properties are longtime family homesteads, and which are owned by recent city transplants. It pains him to imagine these homes — not to mention hardwood forests and potential archeological sites — destroyed.

The Marvin Nichols is a major part of the region’s latest water supply plan, written to accommodate an estimated population of 14.7 million in 2070.

Yet growth is only one of the looming challenges for the water supply in North Texas. The other is human-caused climate change, leading to a rise in extreme weather events. The state is unlikely to escape the hotter and longer droughts of the future.

So with the twin challenges of population growth and climate change, how is DFW preparing for its water future — and what are the costs?

Preparing for the unpredictable

Modern Texas water planning has its roots in the drought of the 1950s. Back then, almost 30% of the state’s farms dried up, dust storms suffocated chickens, and wild hogs feasted on weakened cattle, according to an oral history in Texas Monthly. The legacy of that era marks today’s water planning in two key ways.

First, in the wake of that drought, the state created the Texas Water Development Board, charged with developing new water supplies through loans to public entities.

Second, the 1950s drought was (and for most river basins, remains) the “drought of record.” Today’s water planners in Texas are tasked with finding water supplies that can serve projected population growth during a repeat of that drought.

Benchmarking the process to the drought of record, however, leaves something out.

“There’s not a mechanism to incorporate climate change into the regional and state water planning process,” said Jennifer Walker with the National Wildlife Foundation.

In fact, the phrase “climate change” does not occur in the body of the state water plan, although there are paragraphs that mention “climate variability” and future water uncertainty.

Some utilities around the country have said traditional planning — based on one scenario, like a drought of record — will become less and less useful as the climate warms and disasters become more frequent. Walker endorses another approach taken by cities like Denver called “scenario planning,” which identifies a range of possible future conditions. Policymakers choose what to do based on that range.

But the current director of water supply planning at the Texas Water Development Board, Temple McKinnon, said the board does not have the money or the authority to do it.

“Doing scenario planning, that’s a scale [kind of] beyond what this process can accommodate right now,” she said.

Other water managers say they account for climate change without scenario planning.

“Anyone who … does the water supply side of the business, before the words were in vogue, were already dealing with resiliency, and also with reliability and sustainability,” said Kevin Ward, general manager of the Trinity River Authority and chair of the Region C water planning group.

Ward said the state can give regions a special allowance to plan for both the drought of record and a one-year reserve supply in existing reservoirs.

“We’re planning for 1.87 million acre-feet of water when we need about 1.37 [million],” Ward said of the total new potential water supply Region C has identified for development by 2070.

That extra 500,000 acre-feet is, in part, to be more resilient amid climate change, he said.

(An acre-foot can supply six Texans with water for one year. A half million acre-feet is more than four times what the City of Fort Worth used in 2019.)

Planning for extra supply might be good enough for Texas to have enough water in case of a drought more severe than the 1950s. Walker, however, said setting a high water supply benchmark and then building projects like reservoirs to achieve it won’t move the state to be more efficient or resilient.

“I admit that it would be complicated … to do scenario planning,” she said. “But I also feel like it’s going to be a lot more complicated to not be real with ourselves about what’s coming for our water supply.”

Still, Walker and McKinnon both agree the state water board can’t do much on its own to change the current planning process.

That’s because the board’s mandate and funding come from the state Legislature. Texas lawmakers in 2021 did not try to curb the carbon emissions that warm the planet, instead passing bills to bolster the powerful oil and gas industry.

The cost of more reservoirs

The Region C water plan contains hundreds of projects that would increase DFW’s future water supply, anything from new pipelines connecting existing lakes to more infrastructure for treating and reusing wastewater.

But by far the biggest project — and most controversial — is the Marvin Nichols Reservoir.

It comes at a substantial financial and environmental cost. The price tag is currently pegged at about $4.5 billion. Marvin Nichols Reservoir would flood 66,103 acres, and builders may have to acquire twice that or more to mitigate the environmental effects.

The project would subsume 10,156 acres of bottomland hardwood forest and 21,444 acres of forested wetland. A Region C analysis identifies four species federally classified as “threatened or endangered” that live where the Marvin Nichols would be, and state classification ups that to 20 species. (The analysis says there is either zero to moderate potential that the reservoir would impact these species.)

Texas Region C Water Planning Group/KERA News

Of course, there is a tremendous cost to the lived reality of the people who currently reside in the lake’s footprint.

Troy Hardwick of Red River County bought his house 10 years ago, well after the fight over Marvin Nichols had begun. Hardwick said when he was buying the property, no one told him it was within the boundary of a proposed reservoir.

Like so many residents here, he doesn’t think the project is fair.

“They have no problem flooding people out so they can water their lawns and keep their golf courses green,” he said, referring to the Dallas-Fort Worth region. “That just don’t seem right. Just because you got money, more than somebody else, doesn’t mean you can just take their stuff.”

Residents would be compensated for their land, but that doesn’t mean they want to sell.

The Marvin Nichols Reservoir is sponsored by three water wholesalers, including the North Texas Municipal Water District, Tarrant Regional Water District, and the Upper Trinity Regional Water District. Those agencies sell to utilities all across the metroplex. The water from Marvin Nichols Reservoir would serve people from Anna to Benbrook, Kaufman to Chico.

Northeast Texas residents and businesses recently launched a formal campaign, redoubling their efforts against the project.

Some opponents of the Marvin Nichols insist DFW residents could simply use less water. Yet water managers dispute this option, given the high rate of population growth.

How to encourage conservation

Jace Harms pulling weeds in front of his home in Northeast Dallas on August 3, 2021. Earlier this year he ripped out his front lawn and planted a blend of grasses that can survive on the rain that falls naturally.

Jace Harms knew he wanted to save water, avoid pesticides, and still have a healthy lawn after he bought his first house. So the Dallas resident dug up most of the front lawn and planted a blend that included Buffalograss and Blue Grama, both Texas natives.

“Both have a much deeper soil horizon, so the roots go deeper [and require] less water,” Harms said.

Harms’ neighbors have been curious about the experiment, some even commenting on his progress. Yet the watered lawn is still king — at least six sprinkler systems have been installed on his block this year.

Texans clearly love their non-native lawns. Outdoor water use accounts for over 30% of a single-family home’s annual water consumption, according to a 2012 study by the Texas Water Development Board.

The City of Allen’s Water Conservation Manager Gail Donaldson doesn’t think a wholesale change to lawns is needed to significantly bring down water use. Her plain message to residents is, you don’t need as much as you think you do.

“If people could just understand that that sprinkler does not need to go every single week, that is going to save huge amounts of water,” she said.

Donaldson said there was more attention to water conservation among residents back during the last drought, which spanned 2011 to 2015. At the time, Allen and other cities imposed strict limits on outdoor watering with sprinklers, like restricting it to twice a month.

Today, Allen restricts sprinkler use to two days per week, but hasn’t issued a water use citation since 2015, according to a document provided by the city. Likewise, the City of Plano hasn’t given out violations since 2015, a spokesperson said.

Yet simply increasing fines and enforcement of watering rules won’t change water use, Ward said, because people will be less likely to cut back after a dictate from on high.

“If you make something mandatory, you lose ownership,” he said. “It’s a regulation. It’s someone else’s problem.”

One way cities try to get residents to cut water use is by raising the price after a customer meets a certain threshold. Yet R.J. Muraski, an assistant deputy with the North Texas Municipal Water District, said “water’s very, very reasonable right now in the Metroplex.”

NTMWD sells water to its member cities for $2.99 a thousand gallons, about a quarter of a penny per gallon.

Like so many parts of creating a sustainable society, the big lift is changing how people live.

“Conservation comes with habits,” Muraski said. “Can you tell me you can for certain change somebody’s behavior between now and the future? I’m not sure you can say that, and neither can I.”

‘We’re in limbo’: DFW’s uncertain water future

When another drought descends on the metroplex, people may have to learn quickly how to live with less.

Walker pointed to the example of a school in Wimberley ISD, where captured and reused water offsets about 90% of what the building would otherwise need. Innovations like these, she said, would boost our collective “water intelligence” and reduce the strain on our potable water sources.

Yet Muraski, Ward, and Donaldson all insisted no level of water conservation would make a new reservoir like Marvin Nichols unnecessary.

Troy Hardwick, who lives in the footprint of the proposed Marvin Nichols Reservoir, said it’s frustrating not knowing what will happen with his home. The lake is still far from a sure thing, since it needs to secure permits and acquire all of the relevant land.

“We’re in limbo,” he said. “If you’re gonna take my land, write me a check and take it. Don’t just keep me in limbo.”

Meanwhile, many of his neighbors say they’ll see the builders in court.

These fights are unlikely to disappear as long as climate change and relentless growth persist. The state and region will continue to face questions about what is sustainable — and fair — as they search for future water.