The Marvin Nichols Reservoir remains a theoretical project that its proponents believe will solve the Dallas-Fort Worth’s water problems for what they hope would be forever.

However, the reservoir is no closer to becoming a reality now than it has over the past 30 years it has been the subject of heated debate throughout North and Northeast Texas.

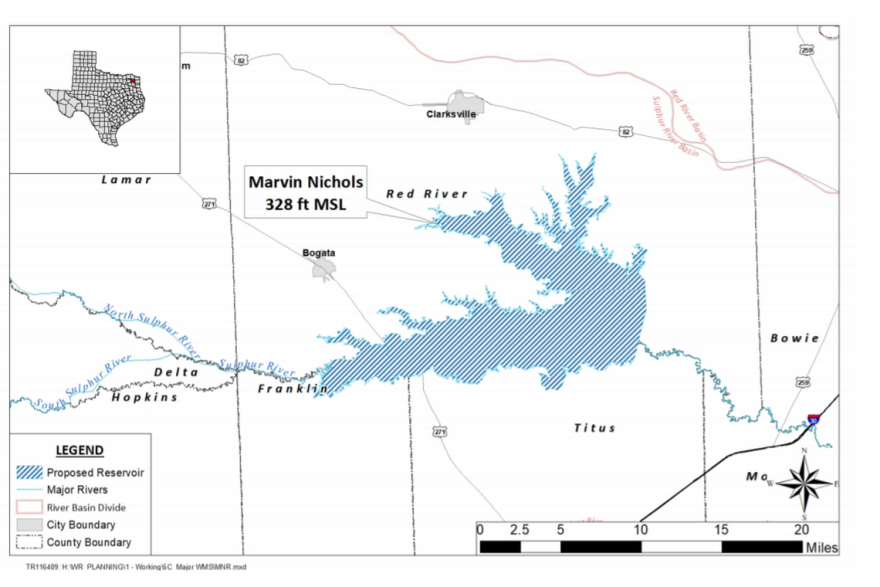

The lake being pitched would put about 66,000 acres of prime hardwood forest underwater. Therein lies the crux of the opposition to the reservoir project. The loss of the hardwood would disrupt the region’s habitat, it would deprive property owners of their livelihood and would deprive the timber industry that is vital to the economic well-being of many communities throughout the region.

That appears to lie at the heart of the opposition to the reservoir.

Water planners, though, argue that the reservoir is necessary to quench the thirst of potentially millions of North Texans who will settle eventually in the Dallas-Fort Worth area. Without the water they will need, the region cannot possibly grow toward anything approaching its potential.

Author and conservationist David Marquis sees alternatives to reservoir construction as avenues toward future economic growth and development. “Were reservoirs once the solution?” he writes. “Yes, they were. They were close to major population centers and much more economical to build. The proposed Marvin Nichols reservoir would cost us billions of dollars and be 150 miles away” from the Metroplex.

Marquis also is concerned about potential loss of productive agricultural real estate. “There also is a more question to be reckoned with,” he writes. “Building the Nichols reservoir will flood 66,000 thousand acres of productive agricultural land, including thousands of acres of hardwood forest. It would inundate rural school districts, displace families that have been on that land since the 1830s, destroy their homes, wash away the graves of their ancestors. In addition, it would require at least another 130,000 acres of land to be set aside to meet federal mitigation policies so that, in total, building the reservoir would take more than 200,000 acres out of production. This would have a devastating effect on Northeast Texas’ economy.”

Some of the alternatives to reservoir construction involve greater use of groundwater, according to Marquis. “We have constructed wetlands, underground storage in aquifers and filtration systems that can clean polluted water, including wastewater, to potable standards,” Marquis notes. He notes that utility companies use “educational initiatives to teach about water usage” and said that “in Texas, we can also filter the vast amounts of brackish water that exist under much of our state. Indeed, for much of Texas, the future of water is filtration. For those of us in the Dallas-Fort Worth area, we can also bring water from under-utilized existing reservoirs, such as Lake Toledo Bend.”

The Marvin Nichols project is so huge it has two water district sponsors, the Tarrant Regional Water District and the North Texas Municipal Water District. Indeed, the NTMWD is in the midst now of building the Bois d’Arc Lake Reservoir in Fannin County, which will provide roughly 16,000 surface acres of water to the region. NTMWD recently completed its mitigation work on land at Riverby Ranch, restoring much of the land to its original habitat. NTMWD claims success in welcoming back wildlife to the region as well.

Of particular concern to critics of the reservoir is the loss of what they call “bottomland hardwood forest” land that many deem essential to the timber industry that harvests the wood for use in home construction.

The fight over the Marvin Nichols project has raged seemingly forever. It would run along the main stem of the Sulphur River. The project was proposed in 1984 and ever since the proposal that came forward, the site has been embroiled in disputes and challenges. As the Dallas Morning News stated in an editorial: “Serious and considerate evaluations were needed, but the time has run out. The future generations of this region will suffer. The reservoir would be built on the main stem of the Sulphur River in East Texas.”

The NTMWD foresees a population explosion occurring in North Texas, citing the Texas Comptroller’s Office estimate that the state population will exceed 47 million residents by 2050; the 2020 Census puts Texas’s population at about 29 million.

The Marvin Nichols Reservoir remains a critical asset to help the region deal with that expected growth, according to NTMWD. “The reservoir was conceived to provide water supply for multiple water providers and jurisdictions and is one of a combination of water supply strategies intended to meet the water needs of North Texans,” the district declares in a statement.

The Texas Water Development Board updates its State Water Plan every five years, compiling information from 16 regional water plans to develop its SWP, NTMWD states. The North Texas Region lies within the Region C water planning area. The water district acknowledges the concern for conserving water and for “reducing water demands and making use of existing supplies,” but adds that “it is clear that development of new water supplies is required to meet the future needs of Texas.” NTMWD states that the Nichols project “has been included in the SWP for several decades as a recommended water supply strategy for Region C.”

The NTMWD offers assurances that it intends to deal with mitigation activities required when the reservoir is completed. “The 2021 Region C plan,” states the district, “contains an analysis of the environmental, agricultural, timberland and socio-economic impacts of the Marvin Nichols Reservoir, including the effect of mitigation activities.”

NTWMD notes as well that Bois d’Arc Lake is nearing completion, citing it as the first major reservoir “constructed in Texas in 30 years. The vast majority of lake property for the Bois d’Arc Lake project was acquired from willing sellers and even though the lake is still filling, Fannin County is already experiencing economic benefits from the lake.” NTMWD anticipates future benefit will come to the region surrounding the Marvin Nichols Reservoir.

The water district seeks to offer assurance that it will “continue to act responsibly and prudently in all efforts to evaluate and develop needed water supply projects for our region and Texas. Our future depends on it.”

The Marvin Nichols project took form 38 years ago. There have been endless fights among numerous interest groups on both sides of the debate. There appears to be no end in sight … to the bickering.